Wer sich selbst erhöhet, der soll erniedriget werden

BWV 047 // For the Seventeenth Sunday after Trinity

(Who himself exalteth, he shall be made to be humble) for soprano and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Olivia Fündeling, Jennifer Rudin, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, Manuel Walser, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen, Christine Baumann, Yuko Ishikawa, Christoph Rudolf, Eva Saladin

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Volker Meid

Recording & editing

Recording date

09/20/2013

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Luke 14:11

Text No. 2–4

Johann Friedrich Helbig, 1720

Text No. 5

Poet unknown

First performance

Seventeenth Sunday after Trinity,

13 October 1726

In-depth analysis

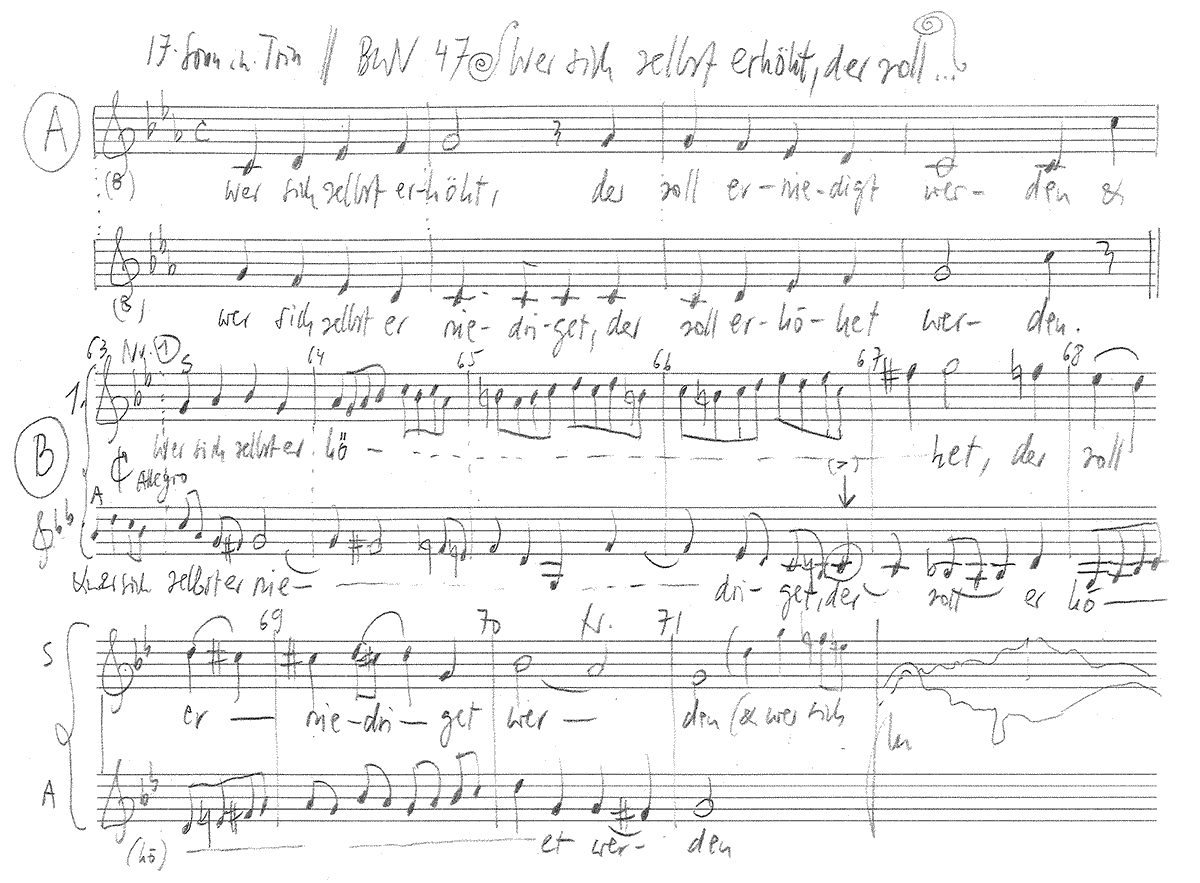

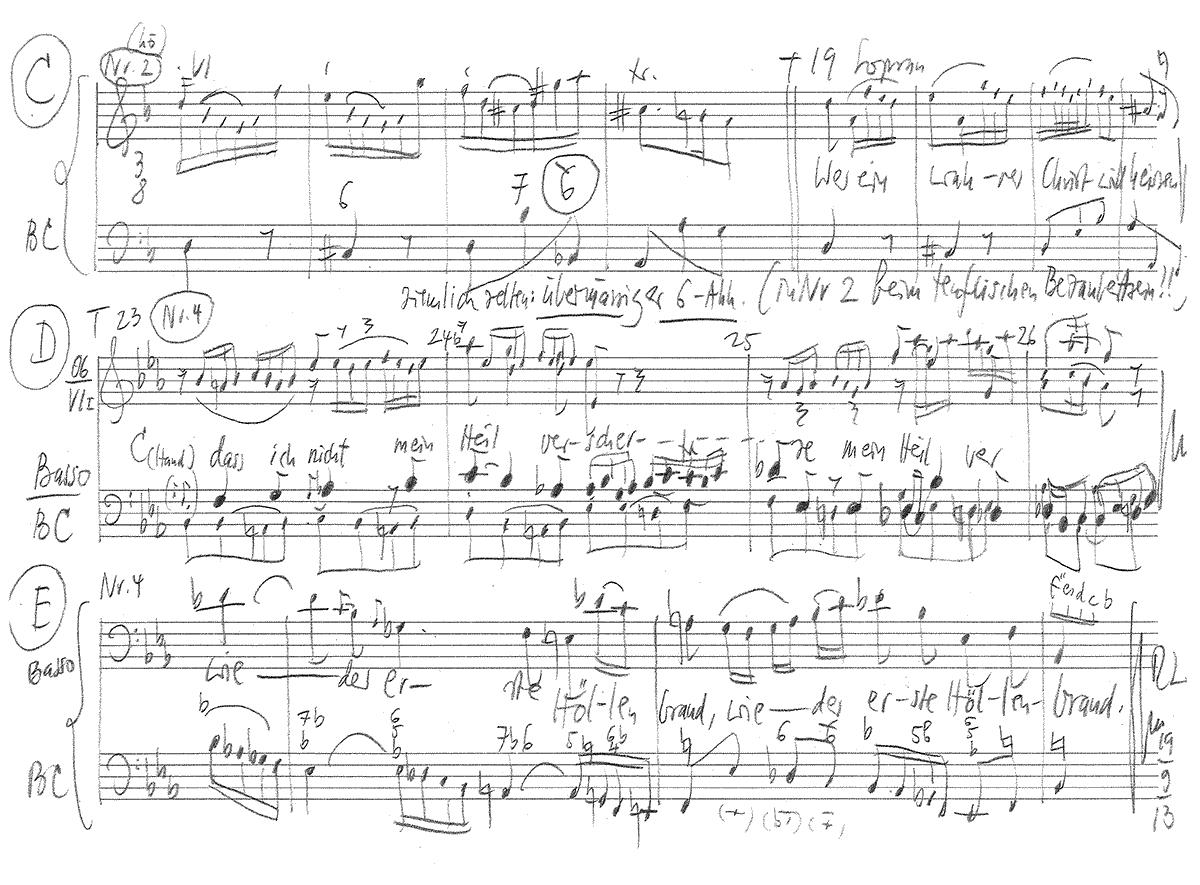

Cantata BWV 47 is Bach’s only composition set to a text by Johann Friedrich Helbig, who in 1720 published a cycle of cantata libretti in Eisenach under the title of “Auffmunterung zur Andacht” (inspiration for devotion). The cantata was composed for 13 October 1726; no evidence supports past conjecture that the work was conceived as an audition piece for Bach’s visit to Hamburg in 1720.

The introductory chorus is based on the antithetical dictum from Luke 14 that pronounces contrasting rewards for human pride and humility; the parable instructs that a guest should avoid taking the best seat at the table and instead wait humbly to be escorted there by the host. From the very outset of the extended introductory section, Bach illustrates the moral peril and weighty consequences of the dictum. Set in the earnest key of G minor, the alternating oboe and string lines evoke an admonitory finger pointed at the listener ere the ongoing exchange of musical materials juxtaposes modest humility and ostentatious exultation. This is followed by a freely treated vocal fugue featuring various voice combinations and layers of orchestral material. This skilfully proportioned setting, which would have made for an equally fine Kyrie in a Bachian Missa brevis of the 1730s, makes clear that in the master’s oeuvre, sensitive appreciation of text is always paired with great musical logic.

In the soprano aria, the instrumental obbligato presents a restless figurative melody over gently-stepping quavers in the continuo line. The scoring of this part for violin, with its urgent phrases and double stops, was apparently chosen for a revival of the work in the 1730s; indications in the score and later comments by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach suggest that the original version was, however, written for obbligato organ. The significance Bach assigned to this obbligato is demonstrated by both the independence of its lines and its place in the extended coda. The soprano part, by contrast, adheres closely to the text affect of the continuo part, a decision that heightens the condemnation of haughtiness and pride which erupts in the contrasting middle section.

In the accompagnato recitative, the bass soloist does not mince his words when he describes humankind as “Kot, Staub, Asch und Erde” (excrement, dust, earth and ashes) – the Helbig original even uses the word “Stank” (stench) in place of “Staub” – and thus highlights the gulf between mere mortals and divine majesty. Indeed, that the creator lowered himself out of love for the vain children of earth gives them no claim to favourable treatment! Here, the icy string accompaniment does nothing to soften this scolding, but reinforces, like a pulpit chiselled of sound, the distance between message and recipients. In the closing transition to E-flat major and its comforting promise, a new warmth then emerges, lending the tender violin and oboe lines in the following aria an enchanted glow. Here, the bass descends from the pulpit, joins in the prayer and pleads with confiding trust: “Jesu beuge doch mein Herze” (Jesus, humble yet my spirit). This through-composed setting would also make for a pretty sonata-quartet, for instance with an obbligato bassoon – something that Telemann, who set the entire Helbig libretto cycle to music, had a penchant for.

With a return to the key of G minor, the closing verse of the hymn “Warum betrübst du dich, mein Herz” (Why art thou troubled, O my heart) reaffirms rejection of earthly concerns and “zeitliche Ehren” (temporal praise). In this setting, the words of “herbe bittre Tod” (painful, bitter death) are set with such distinction that even the sleepiest churchgoers would have been jolted awake in their pews. Indeed, chorale settings in the hands of Bach are never the work of a mere copyist.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Wer sich selbst erhöhet, der soll erniedriget werden,

und wer sich selbst erniedriget, der soll erhöhet werden.»

2. Arie (Sopran)

Wer ein wahrer Christ will heißen,

muß der Demut sich befleißen,

Demut stammt aus Jesu Reich.

Hoffart ist dem Teufel gleich.

Gott pflegt alle die zu hassen,

so den Stolz nicht fahren lassen.

3. Rezitativ (Bass)

Der Mensch ist Kot, Staub, Asch und Erde;

ists möglich, daß vom Übermut,

als einer Teufelsbrut,

er noch bezaubert werde?

Ach, Jesus, Gottes Sohn,

der Schöpfer aller Dinge,

ward unsertwegen niedrig und geringe,

er duld’te Schmach und Hohn;

und du, du armer Wurm, suchst dich zu brüsten?

Gehört sich das vor einen Christen?

Geh, schäme dich, du stolze Kreatur,

tu Buß und folge Christi Spur;

wirf dich vor Gott im Geiste gläubig nieder!

Zu seiner Zeit erhöht er dich auch wieder.

4. Arie (Bass)

Jesu, beuge doch mein Herze

unter deine starke Hand,

daß ich nicht mein Heil verscherze

wie der erste Höllenbrand.

Laß mich deine Demut suchen

und den Hochmut ganz verfluchen.

Gib mir einen niedern Sinn,

daß ich dir gefällig bin!

5. Choral

Der zeitlichen Ehrn will ich gern entbehrn,

du wollst mir nur das Ewge gewährn,

das du erworben hast

durch deinen herben, bittern Tod.

Das bitt ich dich, mein Herr und Gott.

Volker Meid

“When writing poetry was still a craft”

A look at zeitgeist, rhetoric, stylistics and poetology in the cantata texts sensitises us to changing, but also standardising demands on the skill of poets between the early modern period and the early Enlightenment. What remains the same, in the sense of a stylistic unity that transcends the ages, is Bach’s music.

“He who exalts himself shall be humbled, and he who humbles himself shall be exalted”: This sentence, which occurs several times in the Gospels, with its antitheses provides the content and formal structure of the cantata. Humility – arrogance, salvation – hellfire, poor worm – proud creature, Lucifer-inspired suberbia of man on the one hand, divine humiliation for “our sake” on the other. Just as the cantata begins with a biblical quotation, the vocabulary and imagery of the following cantata sections also derive directly from the biblical text or allude to it: Excrement, dust, ashes, earth, worm as ciphers for the transience and nothingness of man are found here quite frequently. And references to Lucifer, hell, Christ’s suffering and calls to repentance are also part of the usual repertoire of spiritual poetry, like the antithesis of temporality and eternity in the final chorale.

These are not new insights, nor is the observation that the text of this cantata is no poetic masterpiece. But it can serve as a starting point for some thoughts on the style of Bach’s very different cantata texts, their poetological presuppositions and their stylistic procedures. I will confine myself to Bach’s sacred cantatas, those of the baroque composer Bach, and ask myself the question: how do the texts set to music relate to this stylistic classification, how ‘baroque’ are they?

The texts of Bach’s cantatas were composed over a period of more than two centuries, between 1523 and about 1740, so they come from different historical and stylistic periods, from Martin Luther and the Reformation to the Baroque with texts by Paul Fleming, Paul Gerhard or Johann Rist, and finally to the Enlightenment. Language, style and metrical specifications are correspondingly different – and the cantata form itself also changes and takes on elements of opera such as recitative and dacapo aria. In addition, one has to think of the non-simultaneity of the arts: while the literary Baroque in the German-speaking world has been gradually replaced by Enlightenment tendencies since the end of the 17th century, Baroque architecture is still in its infancy, and in sacred and secular music the high points are still to come: Bach and Handel were born in 1685.

In modern terms: collage technique

Now the texts of Bach’s cantatas, which come from the various epochs, are by no means uniform in themselves either. In many cases, the centuries intermingle and provide stylistic contrasts: for example, the final chorale of the cantata “Wer sich selbst erhöhet, soll erniedriget werden, und wer sich selbst erniedriget, der soll erhöhet werden” is from a hymn from around 1560. It is thus 160 years older than Johann Friedrich Helbig’s main text from 1720. The differences in language – not in content – show this clearly enough. To use modern terms, one could speak of collages or montages.

On a smaller scale, the practice of montage is repeated in the individual texts or parts of texts themselves: Part of the essence of the countless Protestant spiritual songs of the early modern period is their close reference to the Bible in terms of content and language. After all, their authors were not primarily committed to poetry, but to the new doctrine and its practice and dissemination – with the result that many song or cantata verses have the character of a mosaic work from (at least at that time) familiar set pieces from the Bible or also other songs.

Protestant language and literature reform

So if, despite some 200 years of textual history, the impression of a certain monotony may sometimes arise, this is due to this common tradition, the binding guidelines of spiritual practice and the functional character of the poetry, always oriented towards the fundamental spiritual intention of effect. This also means that the sacred texts of the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries are based on the same poetological foundations, that this commercial art – like early modern literature as a whole, but also music – is shaped by the principles of rhetoric. Here, linguistic expression is guided by the intended effect. And in the case of sacred song poetry, this is aimed at instruction and edification, for which, in turn, the low, simple style, the sermo humilis, is considered appropriate according to the traditional rhetorical doctrine of silence.

With the Protestant-dominated linguistic and literary reform since the 1920s, which is associated with the name of Martin Opitz and is regarded as the beginning of German-language Baroque literature, nothing fundamental changes: the demand for a low style in harmony with the instructional-educational function of the songs and the close connection to the century of the Reformation remains.

Where then is the so-called baroque style of religious song texts after the literary reform? First of all, it consists of the implementation of new metrical and linguistic guidelines, i.e. above all the rule of accentuation according to the ‘natural’ word accent, which is still binding today, and some linguistic modernisations. But in the end, Protestant sacred song and cantata poetry cannot escape the general developments in literature and the history of piety. On the one hand, this concerns the tendency towards increased stylistic virtuosity and pronounced imagery in secular lyric poetry; on the other hand, Lutheran reform theologians, with their concept of a lived piety that transforms people inwardly, contribute to the fact that a new, more emotional tone gradually begins to assert itself in song poetry as well, less dogmatic and instructive, less combative. Pietist emotionalism and the absorption of mystical ideas encourage these tendencies, which intensify in the 18th century and exert a profound influence on the development of intellectual history. They have stylistic consequences and lead to a style that increasingly works with images and rhetorical figures in order to move the listeners or readers to emotional participation, to convey comfort, hope and strength of faith to them by transferring the central events of salvation history to their own lives.

‘Sensible’ and ‘natural’ style of writing

Parallel to this, from the end of the 17th century onwards, a classicist counter-movement gained ground, rejecting the late Baroque art of metaphor and propagating a ‘reasonable’ and ‘natural’ style of writing. These tendencies did not bypass Bach or his lyric poets. After all, he lived in Leipzig, the most important centre of the literary Enlightenment in the German-speaking world in the first half of the 18th century, along with Zurich.

Three examples from the second half of the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century will illustrate the conflicting tendencies I have indicated. In doing so, I emphasise somewhat one-sidedly the tendencies towards baroqueisation – but this against the backdrop of texts that continue the traditional concept of the sermo humilis or even already realise Enlightenment ideas of style.

The first example is the final chorale of the cantata “Es ist ein trotzig und verzagt Ding um aller Menschen Herze” (BWV 176). It was written by Paul Gerhardt, the most famous poet of sacred songs of the Baroque era. The verses from 1653 are simple, the images thoroughly traditional, the intention dogmatically instructive:

“So that we may all at once

to the gates of heaven

and one day in your kingdom

without all end sing,

that you alone may be king,

high above all gods,

God the Father, Son and Holy Ghost,

“the protector and saviour of the pious,

one being, three persons.”

Gerhardt’s simple song style is matched – despite the large time gap – by the actual cantata text by Christiane Mariane von Ziegler from 1725, which is very restrained in style, closely following the biblical text and its message. Ziegler’s aria preceding the final chorale reads:

“Encourage yourselves, fearful and timid senses,

Be uplifted, hear what Jesus promises:

That through faith I may win heaven.

When the promise is fulfilled,

I’ll be up there with thanksgiving and praise…

Father, Son and Holy Spirit, praise,

who is called Triune.”

Ziegler’s closeness to the literary endeavours of the Enlightenment, whose stylistic principles she shares, becomes clear here: Demand for naturalness of expression, rejection of forced words and affected essence – for the enlightened critics, characteristics of the Baroque style. The fluid verse language and the complete absence of images correspond to this. Put simply: while Paul Gerhardt’s simple verses hardly represent the ‘baroque’ style, Christiane Mariane von Ziegler is already beyond it.

The second example concerns another cantata based on a text by Christiane Mariane von Ziegler, “Bisher habt ihr nichts gebeten in meinem Namen” (BWV 87). It too ends with a baroque song stanza from the 1950s; the author was Heinrich Müller, a very popular writer of edification at the time. The theme is consciousness of guilt and trust in God. Here, in answer to the question “Must I be afflicted?” it says:

“If Jesus loves me

all pain is sweet to me

over honey sweet [i.e. sweeter than honey, v. M.]

a thousand sugar kisses

he presseth to the heart.”

This is language that at first recalls baroque Catholic hymn poetry, such as Friedrich Spee or Angelus Silesius, but at the same time also recalls the aforementioned changes in the practice of piety in parts of Protestantism and the accompanying increase in the importance of pietistic and mystical ideas.

Finally, we should refer to some examples of this baroqueisation in Salomon Franck, a contemporary of Bach and Christiane Mariane von Ziegler. Most of Bach’s cantatas from the Weimar period are based on his texts. They are characterised not least by emotive language and rapturously mystical features, but occasionally also by tangible drasticness and realism, as in the cantata “Tue Rechnung! Donnerwort” (BWV 168). At the same time, in the spirit of late Baroque poetics and emblematics, a preference for remote comparisons can be discerned, which requires the listener or reader to have a talent for combination and knowledge, or knowledge of the Bible. This is the case, for example, with the cantata BWV 161, which takes as its theme the longing for death, alluding to an episode from the Book of Judges (14, 5ff.):

“Come, thou sweet hour of death,

when my spirit feeds on honey

from the lion’s mouth.

Make my parting sweet,

do not tarry,

Last light,

that I may kiss my Saviour.”

In the mouth of the lion slain by Samson, according to the biblical text, a swarm of bees settles down. Later, Samson eats of the honey. And the Bible-savvy reader or listener is faced with the task of making the connection between the allusion to the lion episode and the theme of the cantata text: Just as new life and sweet nourishment arise in the mouth of the dead lion, so death appears to man as a sweet parting that leads him to the longed-for goal: “That I may kiss my Saviour.” This form of combinatory relational play is a popular late Baroque literary technique.

In the following recitative of the cantata BWV 161, the metaphorical mode of expression, but also wordplay and antitheses, underline the baroque-artificial character of the poem. At the same time, the approach to the metaphorical nature of secular poetry loosens the relationship to the biblical text. These verses could be in any baroque rejection of the world, but also in a lament for love:

“World! Thy lust is burden!

Thy sugar is hateful to me as a poison!

Thy light of joy

is my comet, [comets were considered a sign of bad luck, V.M.]

and where thy roses are broken

are thorns without number

to my soul’s torment!”

If I have indicated something like a line of development here – from an emphatically simple, doctrinal style through increasing baroque imagery back to classicist sobriety, as it were – then this applies above all in stylistic terms. However, it does not apply to the chronological course, as the juxtaposition of Franck’s ‘baroque’ texts and Christiane Mariane von Ziegler’s more Enlightenment-retentive verses can exemplarily illustrate. The currents overlap precisely in the transitional phase from the Baroque to the Enlightenment. The simultaneity of the non-simultaneous is to be reckoned with. Only Bach’s music provides the overarching stylistic unity.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).